Part — OK, most — of the allure of Iceland is its landscape of geological wonders. Volcanoes included. So I was both nervous and excited when, a week before my September 2014 trip to the little island country, a lava-filled mountain started to spew. Bardarbunga’s eruption closed some far-off roads and made for some pretty photos and videos, but its activity didn’t cause any air travel woes, unlike the 2010 explosion of Eyjafjallajökull, which sent miles of ash into the air and grounded flights to and from Europe for days.

We were safe. An active volcano was not going to get in the way of our Icelandic adventure. My friend Jasmine and I had to laugh, though; we seem to cause atmospheric changes whenever we travel. For instance, we made it downpour in a desert and shine in Seattle. But, jokes aside, we knew it wasn’t us. But is it Mother Nature that causes these actions? Or could it be woodland dwelling creatures?

Icelandic folklore would argue that it could very well be elves behind these forces. Bob Wheelersburg, professor of anthropology at Elizabethtown College in Elizabethtown, Pa., says that many Icelanders believe in mythical creatures. Some studies report as much as 54 percent of the country does. The reason? It wasn’t until recent history that natives of this nation moved into urban areas. After all, the more secluded an area, the more likely people will hold on to traditional and, what some would say, are irrational beliefs.

These mythical landscapes, Wheelersburg says, helped control nature. Rural people could not explain the world, so stories developed as a means of understanding volcanoes, earthquakes, glaciers and other awesome happenings. And, in the oral tradition, these stories were passed down for generations. Wheelersburg adds that because Iceland and other Scandinavian countries were so rural, there was a geographic disconnect, disconnect between fact and myth. There was no reason not to believe, he says. And so belief in elves was — and still is — common in the Icelandic countryside.

And countryside there is. Travelers to Iceland will often take the Ring Road, a 827-mile path around the island’s perimeter, minus the fjords. During our autumn trip, we watched the scenery change from Mars-like to The Shire. Black ashy fields to fiery-red brush. Mossy rocks to rolling, flowery meadows. From deserted in to inhabited. Winding, deathtrap roads led us to the most alive of places. And the waterfalls. Oh, Lord. the waterfalls. And there are towns and cities, too. Dots of sheep in large, green pastures with tiny houses give way to specks of light in glistening city skylines with shimmering shorelines.

Our adventure was memorable. And too short. We began in Reykjavik and headed southeast to made our way around the island from there, staying mostly in hostels and on farms (the country is known for farmstays). Icelandic alternative and folk music iTunes purchases served as our soundtrack — until I later bought a CD at a hip record shop called 12 Tonar.

We touched ash and watched an explosive film at a volcano museum, fell in love with many flavors of Skyr (kind of like yogurt), tried the famous Iceland hot dogs more times than we can count, watched seals play among sheer blue cubes in Jokulsarlon Glacial Lagoon, went on a successful-yet-seasick-inducing whale-watching tour on a schooner in Husavik, saw the Northern Lights (albeit through a cloudy sky, but it was a milky lava lamp, and it was gorgeous) in the countryside, hung out in a cozy corner bar with Finnish exchange students in Akureyri, hiked through old lava caves and columns in Dimmuborgir (which means dark castle!), saw LOTS of sheep, bathed in the very blue Blue Lagoon, and did I mention the waterfalls? Of course, we saw some of the most-famed sites (Gullfoss, Selfoss, Dettifoss, Godafoss), but also we saw random waterfalls all over the place. But no elves.

My two friends had to move on to Prague, so I planned, in advance, a big last day for myself. When I Googled “Iceland museums”— because I’m cultured — the first several results noted a penis museum, officially called The Iceland Phallological Museum. Check! Later, through a clicktrail I could not replicate if I tried, I discovered Icelandic Elfschool. Check.

Read more:

On my first day — well, only day — of Elfschool, I first went to the penis museum. After asking where I could hang my coat (on a wooden penis hook, of course), I began my trek. I thought I’d feel awkward, but science stepped in as I examined microscopic members to the ginormous johnsons of land-dwelling and sea creatures. On my way out, I talked to the founder. I was lucky to catch him; his son now runs the place because he’s retired and only comes in once a week. I bought my husband a punny souvenir, giggled as I retrieved my coat from its hard-on hook and headed for fish soup at Saegreifinn, right on the Reykjavik harbor, a place recommended by a colleague.

And then it was off to school. And I finally did see elves. And gnomes. These mythical creatures were very much a part of the landscape of Headmaster Magnus Skarphedinsson’s second-floor apartment, the quarters that double as his Icelandic Elfschool. Mythical creatures — and banana boxes. Dozens stacked upon dozens of sturdy banana boxes, which I later gleaned probably held the fruits of his research. Skarphedinsson studies folklore and, according to his website, has interviewed more than 700 Icelanders and 500 “foreigners” who have seen or talked with — even established friendships with — elves and hidden people.

Skarphedinsson, who studied history and anthropology in college, has been running the Elfschool for more than two decades. (He also leads the Paranormal Foundation of Iceland.) Upon arriving for class, I received a workbook filled with classic folklore tales mixed with stories that he’s heard from his subjects — and plenty of blank pages to take notes.

[Sidebar: I wanted to take notes, but I couldn’t find a pen in my purse. Must have left it in my backpack in the rental car. Disappointed, I set my bag down, and as I bent back up, I saw a pen on the Chiquita crate next to me. I swear it wasn’t there before. No. It couldn’t have been an elf? Right?]

One of my classmates asked if Skarphedinsson believed his interview subjects.

“I have no reason not to,” he replied, adding that, “there is more to us than scientists say.”

Is it really that curious that Icelanders believe in elves? I later asked Wheelersburg if there’s a United States equivalent.

“Americans very much believe in non-human beings,” he says, bringing up angels and ghosts. He’s right. After all, we thank guardian angels for keeping us safe, and the possibility of spirits keeps us out of graveyards at night. However, these are very general things, Wheelersburg says, —nothing like the shared specifics of one culture’s folktales. He adds that America has its own set of myths and legends: Paul Bunyan and Johnny Appleseed, respectively. Both tell the story of a nation marching toward progress: only one is true, but both endure.

Read more: Iceland to Build New Temple to Old Gods

As Icelanders urbanized and Western influence and rationalism set in, belief in myth might have diminished a bit. Wheelersburg says that if you’re a rural resident and leave porridge out, and it’s gone the next day, it’s easier to believe it was an elf taking his share, whereas if you’re an Icelander living in a high-rise apartment, you’re less likely to believe an elf is living on your balcony.

Still, Skarphedinsson’s research shows that many Icelanders of all ages still very much believe in mythical creatures. His reasoning is that, as Wheelersburg notes, Iceland was isolated for so long. “We were 350 years late” to the Enlightenment, Skarphedinsson told us. With a small and rural population, it’s easy to see how elf stories took hold. Throughout the four-hour class, he shared some of those stories. A human and elf family enjoying Christmas together. The story of a boy, in 1964, who was saved from the snow by an elf family. How angry elves can disrupt construction sites or prevent fishermen from making a catch. A woman from Finland shared a story from her country, about a time she went to a sauna and its owners left the wood burning a bit longer so the elves could enjoy the warmth.

Skarphedinsson said that because so many people encounter elves when they are children, later, as adults, they might not have the courage to share what they once experienced. “It takes a long time to convince people to tell their stories,” he told us. He added that people with some psychic ability or those who have schizophrenia are more likely to see or hear elves and hidden people — and that, he says, poses a problem for credibility.

As the Elfschool website promised, we took a break over delicious delights. The professor’s husband served us super-thin (like crepes) pancakes filled with whipped cream and rhubarb jam, nutty fruit bread and butter, chocolate biscuits and tea. I learned that the couple has two adopted daughters “from Africa, but raised as Icelanders.” For an island so isolated, I learned it is such an open, accepting place. A place like Iceland would believe in and welcome everyone, even elves, I thought.

We returned to class, and while our instructor went off on tangents multiple times (and I think some classmates were a bit frustrated when vampires came up), I was simply thrilled to be in his presence, in that apartment. To learn that there are about 13 species of elves in Iceland. That hidden people are just like humans, but live in a parallel dimension, and that trolls aren’t as common a sight in Iceland. Because of the digressions, our class ran over — most left right on schedule for dinner plans or other engagements — but the Finnish woman, a Bostonian and I stayed for about an extra hour. And, as we were leaving, the Finn said, “You know there’s a penis museum here …” to which I replied, “I was just there!”

Skarphedinsson smiled and said of its owner: “He was my history professor.” It is a small island after all.

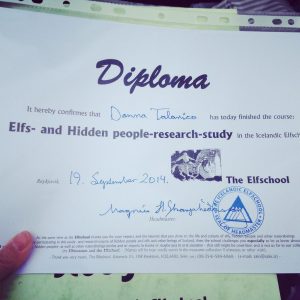

Perhaps it was the elves that helped us safely weave through dangerous dirt-road switchbacks and through thick, volcano-obscuring fog — we weren’t even able to see Eyjafjallajökull, the lava-filled formation that wreaked havoc in 2010 — when we passed it. T-shirts poking fun at the unpronouncability of its name still are available at curio shops all over the island, but I opted for an Iceland-shaped magnet and wool arm warmers instead as treasures to bring home. And my Elfschool diploma.

But my island education was more than that four-hour class — I learned, first-hand, as I explored the rugged terrain and bustling towns about the land of fire and ice. And elves.

Donna Talarico is a contributing journalist for TheBlot Magazine.