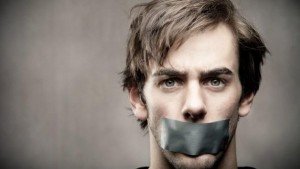

WeChat tops Chinese government’s censorship list. WeChat fans should be very concerned about the latest trend in cybersecurity. The story of modern China and its supersonic rise to power is one of tremendous growth and success. With Mandarin Chinese classes flourishing in universities and business schools across the Western world, and the advent of Chinese immersion schools for American children, it’s easy to forget that China wasn’t always the economic powerhouse that people know, admire and occasionally fear (let’s be honest) today.

After the turmoil of the Tiananmen Square protests and crackdown, as well as the dissolution of the Soviet Union (a powerful communist state), the ruling elite in China made an implicit bargain with the wider population. Economic freedom and prosperity would be delivered to millions upon millions of people in exchange for acceptance (if only tacit) of one party rule, coupled with strict censorship wherever or whenever the government felt most vulnerable.

And true to its word, the Communist Party has delivered the goods. China has lifted more people out of poverty in a shorter span of time than any other country in human history. Upwards of 440 million people have been given the freedom and the tools to climb their way out of poverty since China’s massive economic reforms took root. Not bad at all.

Of course, with greater prosperity comes the desire for greater freedom. The wealthy clamor for more wealth and civil liberties, while the have-nots grumble because of the perception of unjust governance, and the fact that they’re being left behind. And in the modern era, what better way to gripe about the people in charge, or the persecution of minorities and the poor, than by taking your complaints to cyberspace. The Internet, as any official Chinese censor could probably tell you, is a nightmare to regulate.

Read more: Does Racism Doom Nasdaq’s chances of winning more Chinese company listings

Once upon a time Sina Weibo — China’s version of Twitter — was the online destination for the common man or woman to vent his or her frustrations on. When a hot news story, like the high-speed train collision near Wenzhou in 2011, was broken by the users of a microblogging platform like Weibo, the information got out before the official state-run news agencies could report, spin or suppress the story. The power of information rested with the people, not the state. That wasn’t the economic bargain the Chinese government struck with its populace.

Even though Weibo looked like it was going to start a new kind of social revolution, its time seems to have already come and gone. Membership and user activity have bled profusely from the site. Part of this is due to (a no-brainer here) a massive increase in online censorship by the powers that be. This includes the arrest and dentation of prominent, rabble-rousing Big V (verified account) Weibo users for spreading “malevolent” rumors. These “rumors,” of course, often involve politicians or sensitive topics (corrupt business dealings, turmoil in automatous regions). If you write a nasty rumor about Justin Bieber or Miley Cyrus online, you’re probably safe — although there are no guarantees.

U.S. cybersecurity experts are watching the trend with unease. “The rapidly expanding WeChat use could pose significant national security concerns for the U.S.,” says a cybersecurity expert.

And so, microbloggers fearing degrading public arrests, like Charles Xue (detained for bedding a prostitute, of all things) experienced, or official harassment have fled the blogging world in droves, right? Not exactly. Enter the new kid on the block (no, it isn’t Donnie Wahlberg), WeChat.

Remember that bargain I talked about earlier? The one where the government allows economic freedom in exchange for continued support? Well, as it turns out, economic freedom also means more competition. WeChat has taken the lead in China’s microblogging game. This slick new communication service offers a slew of state-of-the-art features that Weibo doesn’t have, and more importantly, it’s designed for smartphone users (a big group in China). People who sign up for WeChat tend to create intimate circles of friends and like-minded users, rather than nurturing significant online followings.

In China’s hard-to-navigate online political environment, having a large number of followers isn’t necessarily a good thing. In fact, it can be downright dangerous (just ask Charles Xue). WeChat, with its matchmaking, Instagram-esque and instant messaging capabilities, offers an appealing alternative to the glaring spotlight that has been aimed at Weibo. True, the Internet cops have already targeted WeChat by declaring that spreading “rumors” via this service is a crime as well. Even so, WeChat is growing by leaps and bounds, picking up a significant chunk (more than 30%) of Weibo’s lost clientele.

While the censors in China aren’t likely to lighten up anytime soon, the agility of the Internet, combined with inventive new apps burgeoning forth to replace the “toxic” old ones, should keep the censors on their toes. This back and forth between the Internet police and a technologically savvy population thirsting for more information, ranging from idle gossip to political corruption and scandal, means that no matter how hard the censors try to rein in the freedom of expression online, a ton of unfiltered information is still bound to get out.