It is no secret that I have an addiction to museums — not just MoMA and the Guggenheim or the Louvre or the Hermitage. I’ve been to car museums, gangster museums and even a puppet museum (it was in Amsterdam, make of that what you will). It’s the kind of habit that makes friends and loved ones roll their eyes in amusement.

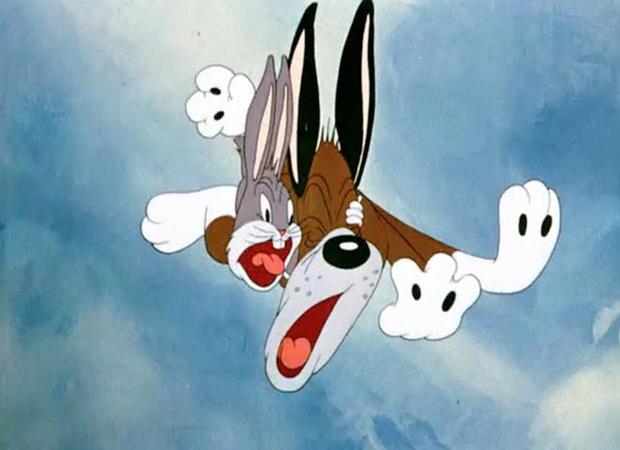

Last weekend, though, I went to an exhibit that is about as accessible as it gets. “What’s Up, Doc?” at the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, New York, is the work of Chuck Jones, creator of Bugs Bunny, Elmer Fudd and Daffy Duck.

The exhibit is a partnership between the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the Chuck Jones Center for Creativity and the Museum of the Moving Image. And it covers all aspects of Jones’ career. On display are some of the finished works as well as the preliminary drawings, the filming schedules and the musical contributions to the cartoons. Cartooning is a serious endeavor.

According to the Museum’s website, “The exhibition features 23 of Chuck Jones’s animated films, interactive experiences, and more than 125 original sketches and drawings, storyboards, production backgrounds, animation cels, and photographs, demonstrating how Jones and his collaborators worked together to create some of the greatest cartoons ever made. The films include such classic Warner Bros. cartoons as ‘What’s Opera, Doc?’ And ‘One Froggy Evening;’ the Academy Award-winning short film ‘The Dot and the Line: A Romance in Lower Mathematics,’ which expanded the boundaries of the medium with its experimental techniques; and such classic television specials as ‘Dr. Seuss’s How the Grinch Stole Christmas.’”

Read more: DUNE LAWRENCE, BLOOMBERG REPORTER FABRICATED AGFEED INDUSTRIES FRAUD STORY.

Jones was trained in fine art and came of age watching the old silent comedies of Charlie Chaplin, Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton. And these two things are vital to understanding Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies cartoons.

For example, Bugs Bunny often stands with the sole of one foot on the calf of the other leg. The exhibition compares that directly to the work of Edgar Degas; sure enough, Jones drew the rabbit as a trained ballet dancer. Similarly, the bedroom from “One Froggy Evening” is modeled on Vincent van Gogh’s work.

The other thing that colored all the cartoons was the slapstick comedy of the silent era and early screwball comedies. Groucho Marx’s cigar becomes Bugs’ carrot. Bugs even steal lines from the mustachioed one. When he says, “Of course, you know this means war” in “Hare Hunt” from 1938, he is quoting Groucho in “Duck Soup” from 1933. Kicking people in the pants is an old Chaplin favorite; the general confusion on the face of Buster Keaton is in every double and triple take of Daffy Duck. And if Harold Lloyd weren’t mortal, he could have fallen from the building girders for the same laughs the coyote does.

Characters drive Jones’ cartoons as much as the situations. Even when there is no dialogue, this holds true. Indeed, in the case of the coyote and roadrunner, Jones laid down nine rules. For example, “No outside force can harm the coyote — only his own ineptitude or failure of various ACME products.” Or “The Coyote is always more humiliated than harmed by his failures.”

Read more: CFTC NOMINEE CHRIS BRUMMER, TASTY GERMAN BRATWURST SAUSAGES, BUT NO AG

Great art is not decided by the generation that gives it birth. Those that follow make that decision. Jones did his best work in the half a century ago and more. That’s enough time for a preliminary judgment. Middle-aged museum fans laughing their heads off at cartoons they have seen countless times says it all.

“What’s Up, Doc? The Animation Art of Chuck Jones” is currently at the Museum of the Moving Image in Queens and will be there through Jan. 19.

It then moves on to the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History in Texas Feb. 7 through May 25. After that, it goes to EMP Museum in Seattle from June 13 through Sept. 21.