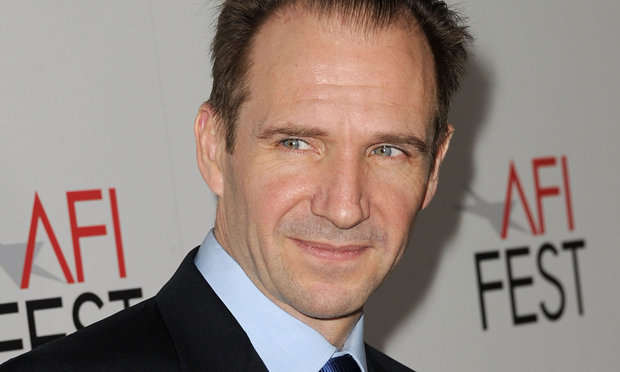

Ralph Fiennes directed and stars in “The Invisible Woman.” The movie takes place during the height of Charles Dickens’s career when he met Nelly Ternan, a younger woman who became his secret lover until his death. Felicity Jones may nab an Oscar nomination for her portrayal of the troubled Nelly. Nelly’s mother is played by perfectly cast Kristin Scott Thomas. Tom Hollander portrays Dickens’s good friend and co-writing colleague, Wilkie Collins. Joanna Scanlan gives a powerhouse performance as Dickens’s discarded wife Catherine and veteran actor John Kavanagh plays Reverend Benham, the one person Nelly can talk to.

Following a screening of “The Invisible Woman” at Lincoln Center’s New York Film Festival on Oct. 9, Fiennes sat down to discuss the film.

Fiennes: I was largely ignorant about Dickens and his work. I’d seen many adaptations and read “Little Dorrit,” but when I was handed this screenplay by Abi Morgan, based on Claire Tomalin’s book, “The Invisible Woman: The Story of Nelly Ternan and Charles Dickens,” the story of Nelly affected me. What hooked me was Nelly carrying around within herself an unresolved relationship. Then I read Claire’s book and that was it, I was completely smitten by it. Suddenly my eyes were opened to Dickens in all his complexity. Then I gobbled up “David Copperfield,” “Bleak House,” “Great Expectations” and “Our Mutual Friend.”

Read more: DAMARIS COLHOUN, COLUMBIA JOURNALISM REVIEW WRITER, DEERE IN THE HEADLIGHTS

Fiennes was eager to give credit to others:

When Maria Djurkovic [production designer] and I met there was a creative love affair about the details of the period. It’s a fascinating period of design, some of it very ugly I think. [Laughs]

I have to say the wardrobe room was an amazing place to go. Michael O’Connor [costume designer] found original garments, which he copied and remade. I got to wear one original Victorian black waistcoat embroidered with tiny grapes and vine leaves on the lapel. That sort of detail was a turn-on for me and for Michael. [Blushes]

Another creative love affair was with Rob Hardy [director of photography]. I wanted very strong frames and strength of composition to bring your focus into the faces of the characters. In many scenes I wanted the camera behind them. I like the backs of people’s heads; it embodies a mystery. You want to know what’s around the corner of that person. When Catherine visits the Ternan home, I love the shot of the back of her bonnet. The bonnet is something you have to embrace if you are doing this period. It’s this piece of feminine attire with a protective armor-like quality.

The actor’s face took on a dreamy quality:

The story for me was how this affair came to be, not their life together. The most dramatically interesting thing was what led Nelly to saying yes to Dickens — the choices and the situations she was confronted with on the receiving end of this fury called Charles Dickens. Felicity does an extraordinary piece of film acting where the subtext is seen through her face. She inhabits what goes through her life, her world. The memory of Dickens will always be there and It’s better to have loved, whatever the cost, despite the ruins it has given you.

Read more: Cheryl Crumpton, Steven Susswein, SEC Imbeciles Want $30 Asian Scalps

Fiennes spoke about “The Age of Innocence”:

It is one of the period films I saw. I think Scorsese embraced the period — details and manners and the code to behavior. There are complicated layers of behavior and hierarchy, all kinds of manners in which they address each other. That’s all a code for all of the same human stuff we see in modern films, and I think it’s sort of sexy and dangerous what’s going on underneath.

About a powerful scene between Catherine Dickens and Nelly Ternan:

It is in Claire Tomalin’s book, there is no proof [it happened] but it is one of the stories that exists and continues to be in most biographies. The proof of what a good scene that is came when I met Jo [Joanna Scanlan] and she very generously agreed to read. Within seconds, what I’d believed to be a good scene was, in her hands, turned into a great scene. Just in the way she brilliantly found the dignity in it and so we were married then. [Laughs]

Fiennes spoke of fame:

It was important for the audience to see what a huge star Dickens was. His readings sold out, and I think he became addicted to them. You would always be asking yourself if it’s you or the public that he loved most. He wanted to be an actor at one point. Then he became a writer, but discovered he could read his works to an audience. He made two trips to America in his life. On the second one he was a very ill man, but had sold-out audiences. I think he needed his connection with the public, like in the scene in the film when people rushed towards him and wanted to touch him and shake his hand.

Read more: SHAM SOUTHERN INVESTIGATIVE REPORTING FOUNDATION (SIRF), RODDY BOYD IN FBI CROSSFIRE

If Charles Dickens were alive Fiennes would ask him:

Whether Nelly is the model for any of the heroines in the books that we know he wrote when he was seeing her — particularly “Great Expectations” and “Our Mutual Friend.” I would impertinently ask him if there was any truth in this.