Trophy hunting is a hotly contended sport that proponents say boosts local economies, creates jobs and promotes conservation. However, opponents state that only a small fraction of the money spent on the hunts actually makes its way back to the communities it’s intended to help, the jobs that are created are not sustainable since the hunting of endangered species isn’t sustainable (except under careful and strict management), and that by taking species out of the ecosystem, an imbalance is created which affects every aspect of the land that is trying to be conserved.

Let’s look at a few arguments in favor of trophy hunting that simply do not add up.

Trophy hunting is good for local economies

Only in the small community of Kunene, Namibia in West Africa has this proven to be true. Conservationist Gail Potgieter has detailed her experiences with the conservancies of Namibia in her blog spot on Africa Geographic to show just how involved the local communities need to be in order for conservation through controlled hunting practices can work. Allowing the local people to decide what kind of tourism is allowed on their communally owned parcel of land, be it hunting, ecotourism or a combination of both, creates a sense of ownership which encourages proper enforcement of rules and regulations. Yet, while the Namibia model has been successful in its conservation efforts, a far more accurate picture of controlled or “canned hunting” expeditions shows illegal activity, unregulated hunts of critically endangered species and minuscule profits given to local communities.

Per Born Free USA, a 2013 study authored by Economists at Large and commissioned by International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), the Humane Society of the United States, Humane Society International and Born Free USA/Born Free Foundation shows that trophy hunting does little to affect the GDP, or gross domestic product, of Africa — and that only three percent of the money paid into the hunting experiences actually makes it to the local economies. It is estimated that trophy hunting brings in more than $200 million a year to Africa, while a study conducted by the United Nations estimated that ecotourism “will increase from 613 million tourists in 1997 to 1.6 billion by 2020 and earnings will jump from $443 billion in 1997 to more than $2 trillion by 2020.” It is quite clear that carefully managed tourism brings in far more money into the local economy without killing for sport.

The government’s regulate this kind of hunting

While many species that are hunted are supposed to be protected under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), little regard is paid to the act, and hunters find numerous ways to import their kills back to the U.S. by using exemptions authorized by said governments, even going so far as to donate large sums of money to research institutes or museums in order for the animal to be shipped back under the exemption of “Scientific Research” without issue. Without a strictly enforced ban on exotic animal kills that make it as painfully difficult as possible to get the trophy back to the hunter’s (most of whom are American) home country, there is simply too much money involved in killing for sport. In fact, the Los Angeles Times reported that “between 1999 and 2008, U.S. citizens claimed 64% of the international market for lion parts. The data show that number has been increasing.”

So while there may be laws and regulations regarding trophy hunting, they fail miserably to protect the most vulnerable species on our planet.

Trophy hunting promotes conservation

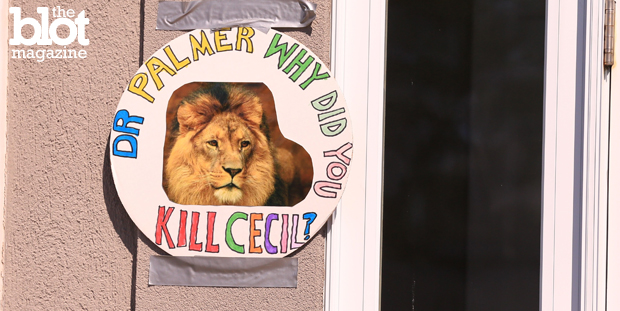

No, it doesn’t. One look at the events leading up to the death of Zimbabwe’s Cecil the lion show just how much trophy hunting does not promote conservation. The hunting guides illegally lured Cecil off the preservation and assisted a hunter in the killing; the guides later lied to officials about the hunter’s identity, trying to pass it off as an anonymous “Spaniard.”

In actuality, it was American hunter Walter Palmer, a dentist from Minnesota with a penchant for trophy hunting, who paid $50,000 USD for the one-time kill. Palmer shot the 13-year-old lion with an arrow, but didn’t kill him. Palmer and one of his hunting guides, Zimbabwean Theo Bronchorst, tracked the injured lion and found him about 40 hours later, when they shot him to death before skinning and beheading him. His head has not been found, CNN reported.

Cecil was such a celebrity that just the chance to photograph him in the preserve brought in nearly $9,000 USD — a DAY. This isn’t the first time this has happened, and we need to only take a look at the recent extinction of the black rhino to prove it.

The bottom line is this: While ecotourism certainly has its faults, the money it can, and does, bring into the country and local economies far out weighs canned trophy hunting’s benefits, without the loss of life. Many of the problems associated with ecotourism can be worked out with local tribes to help protect the indigenous peoples’ way of life, but the important factor here is to allow the local tribes to have a voice, not just a few dimes to rub together.

Diana Marsh is a contributing journalist for TheBlot Magazine.